Inside the

Summer Issue:

Harry Chapin’s

“Ripple” of Influence

Grows Every Day

Jen Chapin Leads Us

On A Lushly-Written

Journey Into Her Life

In “Ready”

WHY Takes Holistic

Approach to Fight

Hunger & Poverty

DMC’s New Disc

Strikes Many Chords

Hard Rock Café

Serves Up Benefit CD

to Fight Hunger

When Howie Met Harry:

Catching Up With

Drummer Howard Fields

Performing Artist

Inspires Audiences

Through Prose

Celestial Cross-Pollination

Yields a Harry Chapin-

Dante Anthology of

Student Essays

Amish Farmers’ Co-op

Finds Innovation in

Simpler Ways

Still Wild About Harry

Behind the CD “Cause”

Do Something!

Click below

to read previous

issues of Circle!

Editor’s Note: The following story originally appeared in Long Island Magazine and is reprinted here with permission.

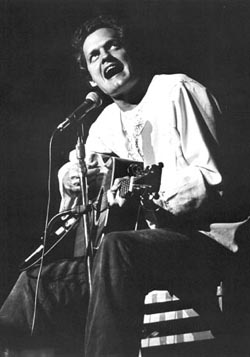

Still Wild About Harry

|

| Photo by Steve Stout |

by Ken Schachter

First would come the phone calls. “Come on. We can do this!” Harry would say in a husky voice that echoed his childhood on the streets of Greenwich Village and Brooklyn Heights.

Then would come the meetings. Tall, rangy Harry, with his angular face, cleft chin and rainforest hair, would stride into the room, fix his searchlight gaze on his target and turn up the voltage. He would cajole, plead and finally deliver the pitch. “Everybody’s worried about obscenity,” he would say. “Hunger is an obscenity. Hunger in America is the ultimate obscenity.”

As often as not, Harry’s prey – be it politicians, businesspeople or entertainers – would succumb. They would join Harry’s team, damn it, and sometimes find the check they had written had a zero or two more than they had planned.

Harry Chapin is dead. The self-described “third-rate folksinger” was killed July 16, 1981. A truck plowed into the rear of his stalled 1975 Volkswagen Rabbit as he tried to coax it onto the shoulder near exit 40 on the Long Island Expressway. He was 38.

But Harry Chapin lives. Not through the quasi-spiritual devotion of pilgrims who visit Elvis’ Graceland or Jim Morrison’s Paris grave. Harry’s legacy is a crystalline commitment to an idea: People should not go hungry. The idea lives, the man lives.

Harry Chapin’s parents, Elspeth and Jim, a jazz drummer, divorced when he was a child. When she remarried, Elspeth Hart moved her family to Brooklyn Heights, then a working-class community, far removed from the upscale investment-banker magnet of today.

Harry’s brother, musician Tom Chapin, recalled a left-leaning family, influenced in part by his grandfather, literary critic Kenneth Burke, and the red-baiting climate of the McCarthy Era of the 1950s. “He was never a communist,” Tom Chapin said of his grandfather, “but he knew all those guys.” The message at home: “Government was dangerous” and “big business was the enemy,” he said. “There was mistrust of millionaires. We threw our lot in with the working class.”

As a child, Harry Chapin was an asthmatic. But he refused to let the condition slow him down, Tom Chapin said.

And even as a child, Harry flashed that super-sized personality. “When he was a kid, we used to say: Two’s company, Harry’s a crowd.”

In about 1957, Tom Chapin recalls, he and Harry heard some music that sent ripples through their lives. He was 12 and Harry was 14 when they first heard a live album by the Weavers, a group that influenced a generation of folk singers.

“We could do that,” Harry said at the time. “That record changed our lives,” Tom Chapin said years later. “One of the things that appealed to us about the Weavers is that they sang about real people and real things.” Other influences were folkies Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger.

|

| Photo by Steve Stout |

Later, Harry Chapin’s own folk-singing career began to blossom. Paradoxically, this was when his career created tension with his wife, Sandy. She “looked askance at him making a lot of money,” Tom Chapin said. “She questioned him.”

In the mirror image of today’s Paris Hilton-worshipping culture, where fame and fortune are their own reward, Sandy Chapin wanted something more.

“So you sell a million records,” Sandy would say. “What does it mean?”

Prodded by Sandy, Harry Chapin did political benefits for candidates like Al Lowenstein, the anti-Vietnam War activist who was elected to Congress. Harry called Lowenstein one of his heroes. But Harry Chapin’s search for meaning hit full stride after Tom Chapin appeared on a radio talk show hosted by Bill Ayres. Tom Chapin suggested that the radio personality talk to his brother, Harry. The two met in September 1973 and hit it off instantly. Ayres came to Chapin’s house for dinner. Then they began hatching ideas.

Ayres told Harry that he had been doing some TV work about the Third World and suggested a benefit concert along the lines of George Harrison’s 1971 all-star concert to relieve hunger in Bangladesh. Rather than Bangladesh, though, Ayres suggested a benefit for Sahelian Africa, a drought-stricken area south of the Sahara Desert.

“There were millions facing death, but there was no talk about it in the United States,” Ayres said.

Harry Chapin’s response? “I’m no George Harrison, but let’s try it.”

That concert never jelled, but in the course of approaching the United Nations and other organizations for help, the two became fast friends and began connecting with activists seeking to stem hunger and poverty.

“We just liked each other personally,” Ayres said. “We were partners. And we were both a little crazy about fighting hunger and poverty.”

Those beliefs led both men to pledge to spend their lives fighting hunger. “We didn’t know Harry’s life would be so short,” Ayres said.

Within two years, the friends recognized that they needed to create a structure for their crusade.

“We’ve got to have an organization here,” Harry said. In meeting after meeting, they kept coming up with the acronym W.H.Y. Why should there be hunger? Why should there be hunger in the richest country?

Working backward, they filled in the first letters of the acronym: World Hunger. The “Y” proved more challenging until they settled on World Hunger Year. People would say: What year is World Hunger Year? Harry Chapin would respond: “Every year until we end world hunger.”

Ayres is executive director and Harry’s daughter Jen is chair of World Hunger Year. She is the next generation of musical and philanthropic Chapins.

A recording artist, she was 10 when her father died, but her impressions remain vivid.

“I use the word hurricane a lot,” she said. “He had this natural sparkle and energy to lead others to grow into their own potential. He was manic, wild energy.”

She remembers her childhood home in Huntington Bay as a “Grand Central Station,” filled with fund-raisers and friends staying overnight or for extended stays. Her father, she said, was a “Pied Piper.” Sometimes Harry would offer to bring concertgoers back to his house for a barbecue if they chipped in an extra $50 for a charity.

Harry Chapin was – and is – known for his story songs and the rabid devotion of his fans. In concert, when he sang Taxi, a song about the unlikely reunion of two lovers, the audience would scream the tagline in unison, “Harry, keep the change!”

Though Jen’s sound runs closer to Norah Jones’ than her father’s, this Chapin also can tuck a social message into the lyrics of a track like “Passive People”: We are passive people, at the end of the day, we let the outrage melt away, it seems that life is so much easier that way.

“I try to be sneaky and not bang people over the head,” she said. “The music is festive, while the underlying message has a little bite to it.”

In the case of Harry’s music, his followers were rabid, but critics were lukewarm and sometimes downright brutal.

In a review of Harry’s 1975 album Portrait Gallery, Rolling Stone magazine called the songs “mundane, vacuous, overblown and clichˇ-ridden.”

Craig Cooper, a singer-songwriter who occasionally served as the opening act at Harry’s concerts, recalled having dinner at the Chapin home.

One of the Chapins’ kids called out: “Dad, there’s a raccoon in the house!”

A raccoon had found its way into a vanity cabinet under a sink. In the process of removing the critter, someone opened the cabinet door and found raccoon excrement everywhere.

Harry’s response: “Gee, I hope he’s not a critic.”

Travel executive Larry Austin used to play golf with Harry Chapin. Much as he did with other parts of his life, Harry took a full-throttle approach to golf. “He used to come to my club,” Austin said. “He’d race in, stuff his mouth with food and race out to play golf.”

Though Harry lacked finesse in his short game, he would “just swing and hit the ball a mile,” Austin said. In fact, the two played a round of golf before Chapin’s fatal drive down the Long Island Expressway.

Once, Austin and his wife bumped into Harry at a play at the Performing Arts Foundation in Huntington. “He pinned me against a wall and said, “I’m making you the president of PAF,’ ” which was having financial difficulties.

To help bail out the organization, Harry and Pete Seeger held concerts in Huntington. But after Harry’s death, the money dried up and PAF folded. “That was one of the real heartbreaks for my mom,” Jen Chapin said. “She was very involved in that.”

Austin then became chairman of the Long Island Philharmonic, another pet project of Harry Chapin.

“He had great friendships with business leaders across the Island,” Jen Chapin recalled. “He was a scrappy folk-rock guy” who could reach out to “these three-piece suit guys.”

At one outdoor North Shore fund-raiser, a rain shower started, Austin recounted. Harry Chapin went to the parking lot in the pelting rain and started knocking on windows and urging drivers to come to the event despite the rain. In one number, Chapin had to dance the hula along with Austin and an executive from Northrop Grumman in grass skirts. “My underwear is still soaked,” Chapin said.

“He would be very convincing and completely tenacious,” Chapin’s daughter said. “It wasn’t about guilt. Let’s make this Island not just about malls and commuting. Let’s cultivate what we have here.”

When he died, Harry Chapin was basically broke.

Harry Chapin did more than 200 concerts a year and about half were “for the other guy,” gigs to support one charity or another, Tom Chapin said. “The last three or four years of his life, I did concerts with him. He’d pay me because I needed it. He’d pay $1,000 a concert. It was cheaper than bringing a band. He was keeping WHY alive.”

At the end, Jeb Hart was his manager.

| How to join Harry’s team Want to join Harry’s team? He’s not here to make his appeal. But if he were, he might say, “I need your help. You have more than enough to eat in your pantry. Not so far from your home, people are starving. Or, don’t let Long Island become a cultural wasteland. Find your checkbook and give what you can afford. Not a penny more, but not a penny less. Make your check out to one of my favorite charities”. Here’s how: |

Hart, Chapin’s half brother, tried to instill some order on Harry’s freewheeling ways. “He was basically unmanageable,” Tom Chapin recalled. “You’d make a plan and he’d go off and do a WHY concert.”

Jeb Hart shared Harry’s philanthropic goals, but they had some classic dustups when he tried to strike balance between business and philanthropy.

“I’d say, ‘Harry, it’s your career that’s enabling you to do this.’”

Harry didn’t listen. “Harry’s answer to any of this was just to work harder,” Tom Chapin said.

As selfless a life as Harry Chapin led, no one is nominating him for sainthood. “It wasn’t just altruism,” said Hart.

“He would have loved to win the Nobel Peace Prize and the Grammy,” said Tom Chapin, who described Harry Chapin as “ambitious in the American way.” It wasn’t a matter of elbowing others out of the way, but of inspiring them to join him in a crusade.

“Not that I’m going to step on your head. His great power was: ‘Come on. We can do this together.’”

Had his brother’s life not been cut short, Tom Chapin said he might have veered toward politics. “He adored performing, but he was getting more and more political.” Harry Chapin would have turned 63 last Dec. 7.

At the funeral, Harry’s older brother, James, was one of the speakers. Nobody could take Harry’s place, he said, but each of us had to try to fill his own shoes.

That spirit, finally, may be Harry’s legacy. Harry’s gone. Now it’s up to those who are left: Come on. We can do this together.

A 25th anniversary tribute for LI?

July 2006 will be the 25th anniversary of Harry Chapin’s death. His close friend and collaborator, radio personality Bill Ayres, wants to mark his passing with an all-star concert on Long Island.

“If I have anything to do with it, we’ll do a tribute concert on Long Island.” Ayres said the Chapin family members certainly would be a part of it, but so would others. Bruce Springsteen, are you listening?

Watch for the Next Issue of Circle! on September 7